PRINCIPIO FURNACE AND THE WAR OF 1812

BY CAPTAIN MICHEAL DODD

The Chesapeake Bay region is rich in fascinating history. This is one tiny morsel.

In the early 19th century, long-distance travel in Maryland and Virginia was accomplished by sailing vessels. Roads were practically non-existent. Commercial ships, private vessels and ferry boats plied the choppy and lovely waters of the Chesapeake Bay. As war clouds gathered before the War of 1812, the country had a small and insignificant navy. The British, meanwhile, had a vast and powerful navy, which soon arrived in the Bay and established complete dominance. Although the country had a minuscule navy, there still were fighting ships available. These vessels were known as “privateers.” A ship was categorized as such if it was privately owned, possessed cannons and was given a license by the national government to engage in combat. These privateers were quite capable of attacking and harassing British merchant ships and stealing cargo. On the British side, their navy was kidnapping American sailors from commercial ships at sea (impressment).

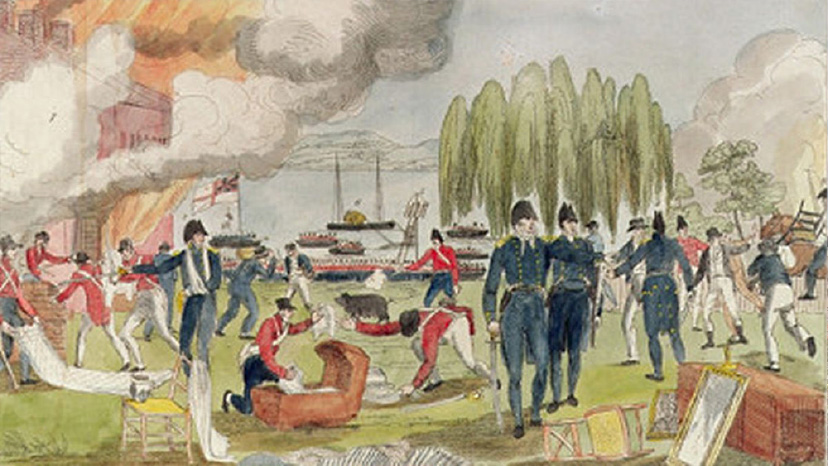

In this era, Americans were sympathetic to the French and were still unsettled with the British after the Revolution. The British point of view was that the Americans were aiding the French, who were at war with the British. In addition, the British correctly suspected that some of the American crews were former British navy men and, therefore, subject to removal. So, they stole our crews, and we stole their cargo. This was one of the underlying causes of the War of 1812. The British Admiral, one George Cockburn, was given the assignment of attacking ports and towns along the Chesapeake Bay coastline. His orders were to capture or destroy any privateer vessels and burn any ports which harbored them. Admiral Cockburn took his assignment seriously, literally, and aggressively. His approach was simple. He would sail into a port on his huge ships-of-the-line with cannons loaded and crews at the ready. If any privateer vessels were in port, he would capture or destroy them. If the town folk resisted or fired on his ships, he would steal any needed provisions and cattle, then set the town ablaze. If the town fathers complied, he would leave the town intact and purchase whatever provisions he required. This was his modus operandi when attacking small ports like St. Michael’s, Georgetown on the Sassafras and Harve de Grace. When attacking cities like Washington, D.C., Baltimore or Norfolk, he would bombard the city into submission and, if necessary, discharge British army troops to attack by land.

The British were quite serious and, at some level, wanted to punish the Americans for their loathsome Revolution some 36 years earlier. It was during the first week of May 1813 that Admiral Cockburn brought his ships to bear on the small town of Harve de Grace in the northern Bay at the mouth of the Susquehanna River. As Cockburn’s men rowed ashore to explain the reality of the town’s hopeless situation, with British guns leveled, one resident did not fully comprehend the precarious circumstance. Or perhaps he got a sudden rush of blood to the head. He was John O’Neill, who later became the lighthouse keeper at Concord Point, where the British attempted to land. O’Neill single-handedly manned a small cannon protecting the lighthouse and began firing at the British. After a few harmless shots, he was subdued.

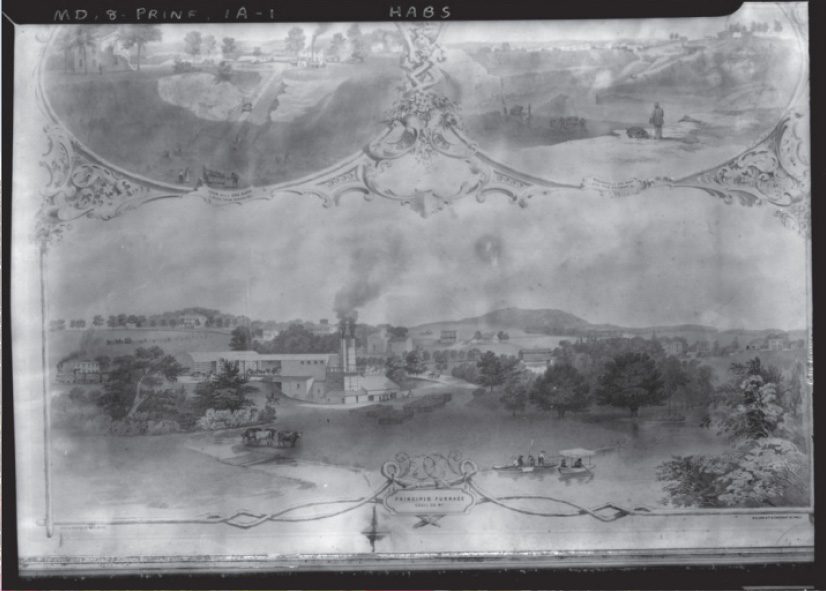

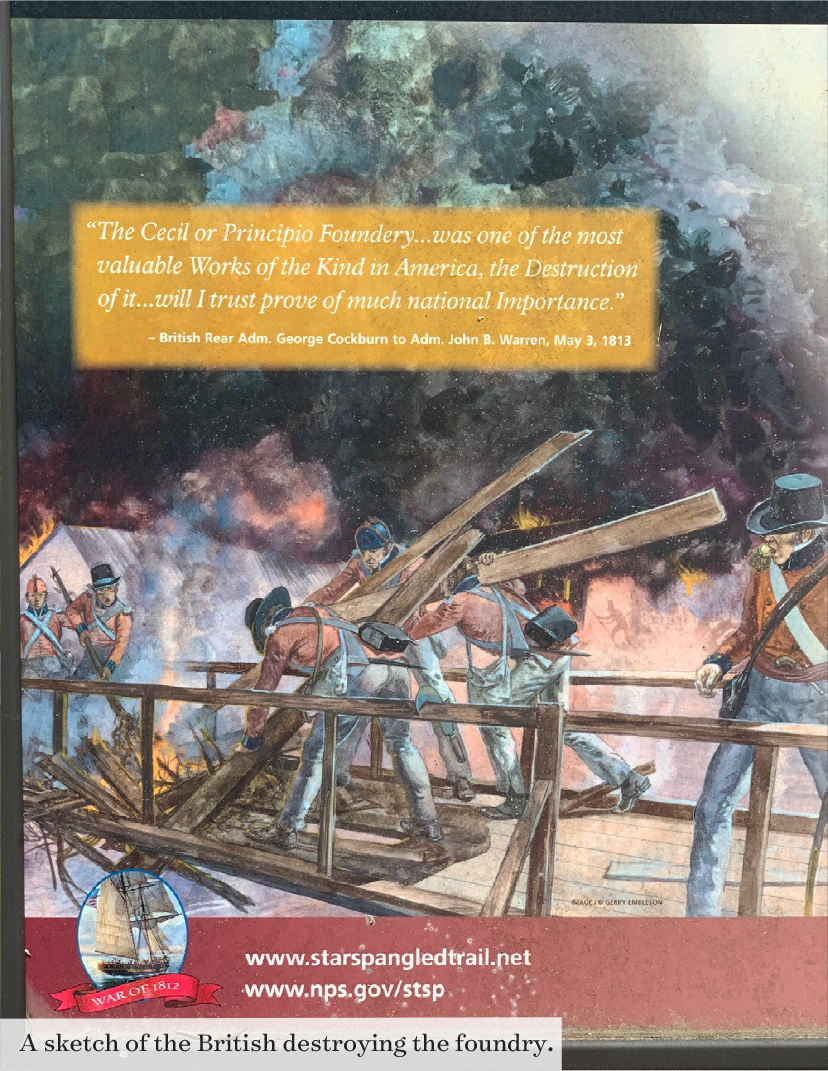

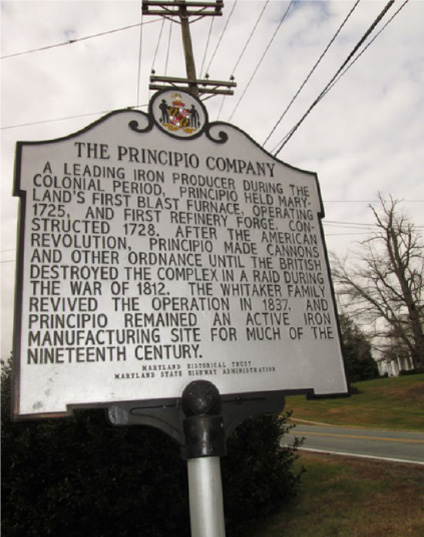

Unfortunately, his action resulted in the burning of the town. Admiral Cockburn had some admiration for the courageous man and later released him. Before Cockburn headed south to attack Georgetown and Fredericktown on the Sassafras River, he engaged in one more destructive act. Across the Susquehanna — about one mile north by land — was the Principio Furnace. Its origin dates back to 1724, when it was built on a small, scenic creek. This iron foundry was an important source of cannons and balls during the Revolutionary War and continued its production during the War of 1812. Cockburn knew of the foundry and set out to destroy it. His men raided the foundry on May 3, 1813, and dissembled and burned it. More than forty cannons were destroyed. This was a significant loss to the American armed forces of the day but was not enough to change the final outcome of the War. Some ruins of the old foundry remain. To this day, a blacksmith and a small private forge still produce ironworks at the picturesque site.