The Teens and the General

BY CAPTAIN MICHEAL DODD

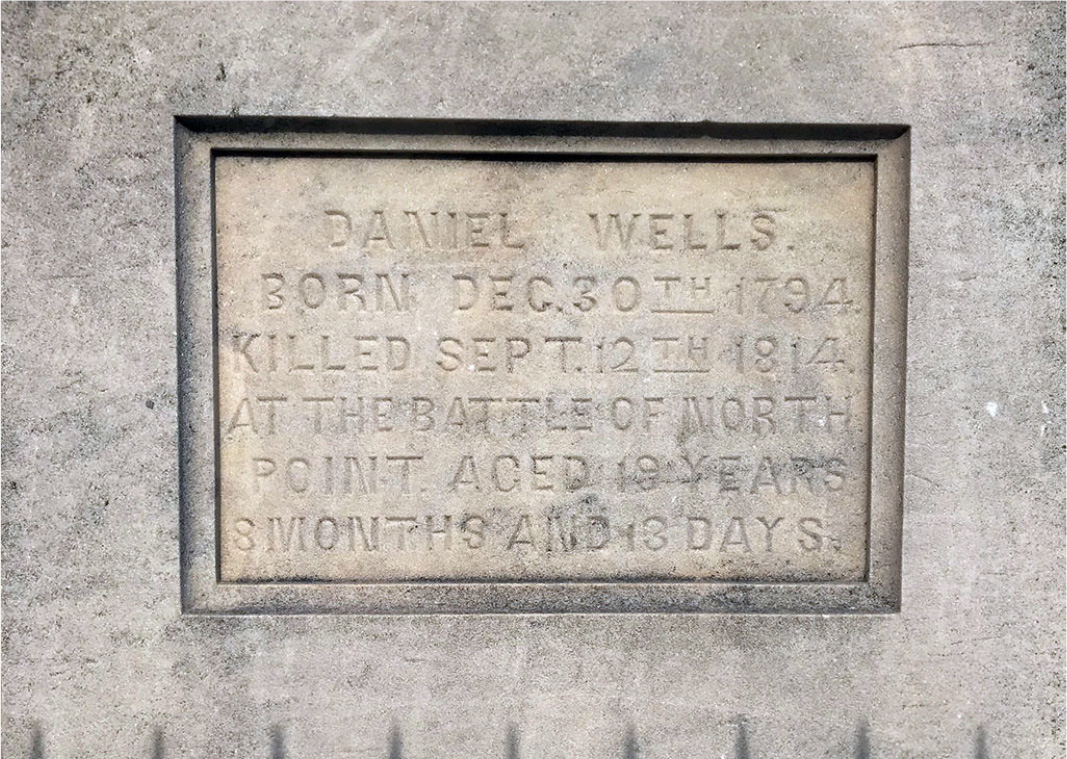

Obelisk Monument dedicated to McComas and Wells in Baltimore.

It is not exactly clear how the wheels of God’s time and space brought these three individuals together on the fateful day of Sept. 12, 1814. For the two young militiamen, their mothers likely made them a quick breakfast, confirmed they each had their horn of gunpowder and their proper moccasins and gave them a hug as they hurried out the door to mix with their regiment Perhaps they

fumbled to the outhouse one more time, then took a last bite of muffin as they grabbed their squirrel guns. Maybe their respective fathers reminded them to aim slowly and shoot true, so they would not waste powder and ball. Perhaps they were neighbors in the center of Baltimore, living just a few lanes apart. Likely, they agreed to meet at a prearranged street corner, with no inkling that they were off to change a tiny block of history.

They were among the youngest volunteers in the Baltimore militia, with a mere 18 years on earth. Henry McComas and Daniel Wells hated the British for their arrogance and power. The British were going to attack and burn Baltimore, as they had done to Washington a week earlier. But the people of Baltimore were at the very least going to give the British a nasty bloody nose. McComas and Wells were determined to take part in the punching.

From a military perspective, the War of 1812 had gone poorly for the new American nation. The British had a powerful navy; the Americans had practically none. The American army was small, motley and poorly coordinated and trained. The officers were hardly stellar. But after the burning of Washington, the local militia was called up, and nearby volunteer farmers, merchants and laborers were determined to defend their home port from the obnoxious red coats of the British Army.

The third man in the trilogy, General Robert Ross, was the perfect British prototype commanding general. He had served in Europe against Napoleon as a popular officer with excellent training and experience.

On this day he was to land his 5,000 troops on the eastern shore of the Patapsco River and march them about eight miles to the city limits to overwhelm and burn Baltimore and destroy the degenerate nest of privateers who had been harassing British merchant vessels for the past several years. The other half of the plan was for the 45 naval ships in the British fleet to attack and crush Ft. McHenry, then sail into Baltimore harbor to assist General Ross with heavy bombardment.

Neither endeavor succeeded. As General Ross and his men advanced, they encountered multiple significant skirmishes with the local militia. McComas and Wells knew this neighborhood well. As the British Regulars with their bright red uniforms approached in the distance, the two clamored up a leafy tree to wait for a target as their colleagues in arms retreated in good order. After a brief interval, their wishes were fulfilled. They remained unnoticed as a line of British troops passed under them. Then an impressive, commanding officer on horseback trotted up near their hideaway. They slowly took aim with their trusty squirrel guns and fired, almost simultaneously. Both musket balls found their target. General Robert Ross crumpled in his saddle. He called out. It mattered little. The teens had done their damage. The general was dead in minutes.

The teenage snipers were murdered immediately as British Regulars trotted up to give aid to the mortally wounded general. McComas and Wells remained breathless and frozen in the tree when multiple shots rang out from the British long rifles. Perhaps they cried out, perhaps they fell, perhaps they quietly became limp in the branches as they took their last breaths. No colleagues were around to aid them. They passed into their final slumber only with each other.

But heroes they were. Their names are memorialized on a Baltimore obelisk dedicated to the pair who relinquished their youthful souls for a greater cause.