The Parson’s

Message

BY CAPTAIN MICHEAL DODD

Today, it is difficult for us to imagine the times and scenes surrounding the War of 1812. We were a small nation consisting mainly of farmers, merchants, and collections of sailors and fishermen. It was easier to travel from state to state via water since adequate roads were nonexistent. Communications were incomprehensively slow, with mail taking many days or even weeks to be delivered across state lines. Our growing nation had no real Navy. In addition, not all residents of the new nation had lost their sympathies with the British. Even years after the American Revolution, many Americans had friends and relatives in England. Supplies were obtained from British companies because they were known for their quality. There was no match for the finery of the British aristocracy. Banking was conducted with British banks. Yet we declared war on England, a powerhouse European nation with the largest and most advanced Navy on Earth. Once war was declared on the British, England found itself engaged in a two-front war, with France in Europe and now with the upstart United States across the Atlantic. The British sent considerable manpower, supplies, and ships against us. They had a special grudge against the ports in the Chesapeake Bay. Many towns, like Baltimore, had sent out privateers (essentially pirates who were blessed by the government) to harass British shipping before the war. Now, the British Navy could take revenge, and they possessed the will and the power to make life miserable for the denizens of the Bay shoreline. And they did.

Their primary engagement was a two-pronged attack on the nation’s nascent capital, Washington, DC. British ships sailed up the Potomac and Patuxent Rivers. American resistance was weak and poorly organized, and the federal buildings in Washington were torched by the British.

The attack was almost too easy for the British. The commander, Admiral Cockburn, hoped his good fortune would continue, and he decided to attempt to replicate the success in Washington by next attacking the epicenter of the privateers, the port city of Baltimore. But first, he needed to provision his ships at the tiny island in the Virginia part of the Chesapeake Bay, Tangier Island.

The British chose this centrally located island to build a provisioning depot and training base. The name given to this site was Ft. Albion (Albion is the Latin term for England). This fort was substantial: it contained barracks for about 1,200 troops, a hospital, parade grounds, officers’ quarters, and stores for ship provisions.

Approaching Tangier Island

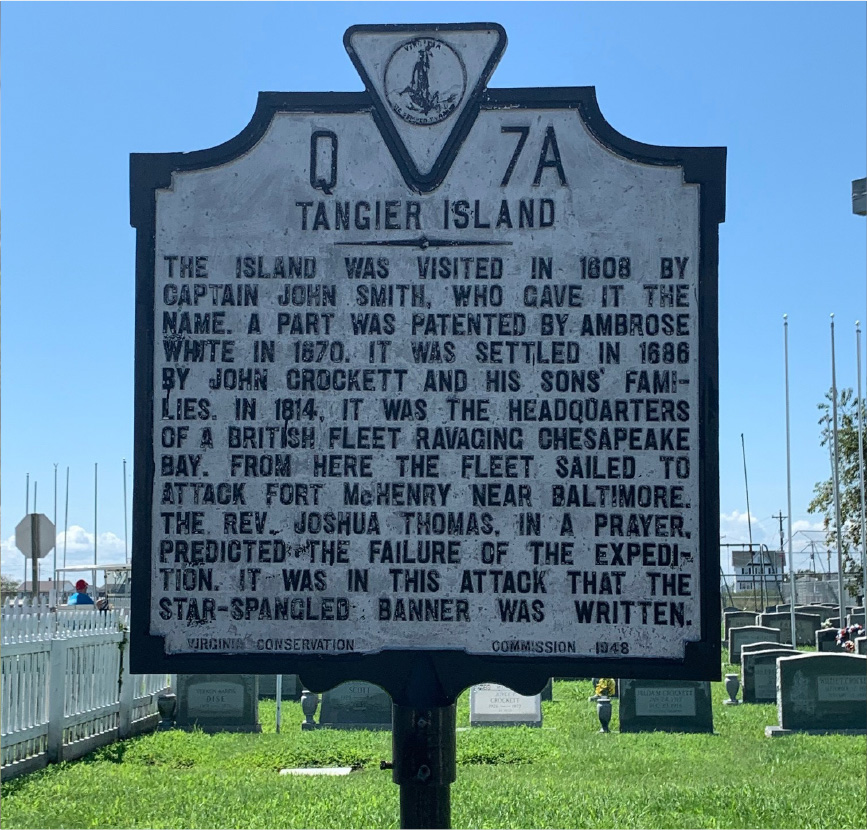

Historic plaque in Tangier Island, which discusses Parson Joshua Thomas

Tangier Island and its northern neighbor Smith Island, had several hundred full-time residents. They lived off the bounty of the bay with oystering and fishing. Each island had a small Christian church and congregation. But there was no full-time resident minister or preacher. The spiritual needs of the souls of these islands were allocated to an itinerant parson. He was paid by donations and ferried between islands by local fishermen. In this era, one Parson Joshua Thomas was the man of the cloth who attended to the islanders. He made himself available to all occupants of the Islands, and this included any temporary residents, in this case, the British.

It had been only a week since their successful attack on Washington, DC. The Navy had provisioned their ships and were ready to sail to Baltimore and burn that pesky city and destroy its privateer fleet. At a church service before departure, Parson Thomas was asked to bless the British ships and crew and offer a prayer for success. Instead, he warned the British that what they planned to do was wrong, and he predicted they would fail. He was correct. Not only did they fail to burn Baltimore, but they lost their most prominent British commander, General Robert Ross. And, of course, the final outcome of the war was not in their favor.

Tangier Island crab pot floats